T.T. Tsui Gallery and the 4th Floor Ceramic Galleries

Introduction

My second talk to the Chinese clients of the consultancy group New Vision was held at the Victoria and Albert Museum on Sunday the 17th of October and consisted of two sessions, one looking at the Room 44, the T.T. Tsui Gallery of Chinese Art and the other – the 4th floor ceramics galleries, rooms 137-139.

This talk was slightly different from the last, where we looked at just one collector (Sir Percival David) and only Chinese ceramics. Here, at the T.T. Tsui Gallery, many collectors have contributed to the displays which comprise various media, from lacquer and bronze through to furniture and jade. In this article, I will look at how these galleries transformed from their previous displays and the factors that contributed to this.

For those more experienced in Chinese art, I apologise at the outset, as this talk is generally targeted at the relative newcomer to Chinese art and serves more as an introduction to the subject, rather than a detailed guide for the well informed. It should also be noted that a greater emphasis in this talk is placed on an examination of the objects themselves, which I hope will encourage visitors to the gallery and to find out more after their visit.

Part 1: T.T. Tsui Gallery

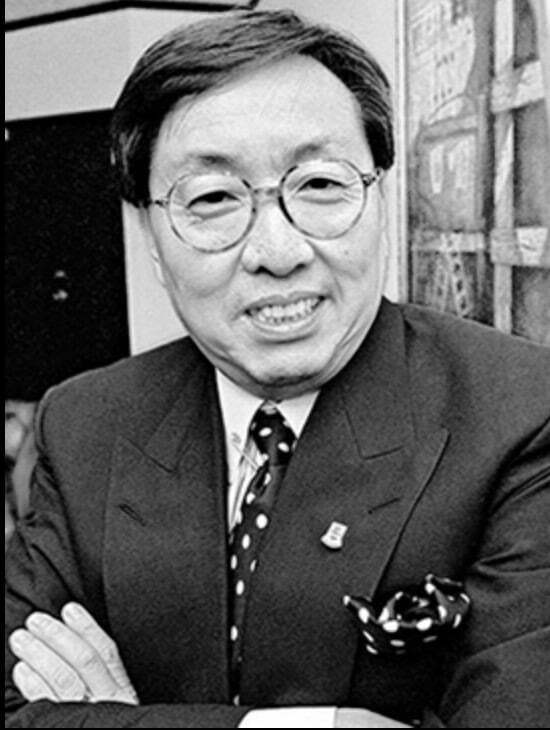

Tsui Tsin-tong (1941-2010)

T.T. Tsui was born in Ji’an, Jiangxi province in 1941. His family were originally from Yixing in Jiangsu province and he emigrated to Hong Kong with them at 9 years of age in 1950. He soon started work as a messenger and handyman, but later his first businesses involved running restaurants and interior decoration companies. He was to become wealthy through the stock market and in property development through the 1970s.

During the 1980s his business empire boomed and he was involved in manufacturing paint products, iron and steel and continued investment in property.

In March 2010 he suffered a stroke in Beijing while he was attending a political consultative conference. He died a month later at 69.

Involvement With the V&A and the Donation of £1.2m in 1988

T.T. Tsui travelled to London in 1988 and whilst there, he spent some of his time visiting its museums. On one fateful day he arrived at the main desk at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) and asked if he could speak to someone in the Chinese art department. Rose Kerr, the current keeper at the time answered the telephone and being able to speak Mandarin, she was intrigued and came out to meet this overseas visitor. She proceeded to give him a personal tour of the Chinese collection in Room 44, which lasted well over an hour.

He was so impressed with his tour, during which he grasped that a re-design was needed, that on the second meeting he offered £1.2m to cover the costs of its re-design and refurbishment. He was the ideal donor in that he gave the Museum pretty much free rein in their refurbishment plans, his only stipulation being that gallery labels should also be in Chinese.

The Previous Approach to the Displays at the Gallery

The Chinese gallery had originally been laid out just after the Second World War and had followed a formal chronological approach, with an emphasis on ceramics. This reflected the traditional scientific/scholarly approach to displays, which classified pieces carefully by their date and respective type of wares. Most light sensitive material, such as paintings and textiles had been taken off display due to the amount of natural daylight entering the gallery from the skylights above.

A New Approach to Displays

Being in the rare position of having all the finance in place at the planning stage, the staff in the Chinese department led by Rose Kerr decided to consult the public to see what they wanted in a new gallery. Two surveys were undertaken, one for the visitors to the gallery and one sent to schools and the Chinese community that lived within 2 hours travel of the museum. 1.

Once all the information from the surveys was analysed, an outline brief was put together for the gallery, which was that they were to be laid out in themes, with no overall chronological framework. Two main areas of interest to visitors emerged: ‘how were things made’ and ‘how were things used’. 2. The curatorial staff decided to focus on the latter and the eight broad themes that emerged were: Ruling, Collecting; Eating and Drinking; Living; Temple and Worship and Burial.

These themes will now be looked at through a number of highlight pieces. In keeping with the first area of interest expressed in the public surveys, an emphasis will be placed on how some of these pieces were made and a variety of different materials will be examined in each of these respective themes.

Ruling

A Large Cinnabar Lacquer Throne, Qianlong Period (1736-1795)

This is one of the most powerful symbols of the ruling emperor and was intricately carved in polychrome lacquer in the imperial workshops (Zaobanchu) in Beijing. It came from Tuanhe Travelling Palace in the Southern Park, around 10km south of Beijing, which was used by Qing emperors for troop inspection and seasonal hunting.

The throne would have stood in front of a matching screen and would have been adorned with cushions. It is decorated with imperial five-clawed dragons and a central panel depicting figures bearing tribute. The throne was looted by Russian soldiers in 1900 and brought to Britain following the Soviet Revolution of 1917. 3. Qianlong period cinnabar lacquer thrones are highly sought after at auction and one sold for £6.1m at Christie’s London in May 2019.

Lacquer

What is it? How was it made? Lacquer is the excreted sap from the Rhus Verniciflua tree. It is applied in many layers (up to 100) and dried in humid conditions. This is somewhat counter-intuitive to what one would expect for drying this material, which hardens to a hard plastic-like finish. It is then carved, through many layers, which can sometimes can be multi-coloured.

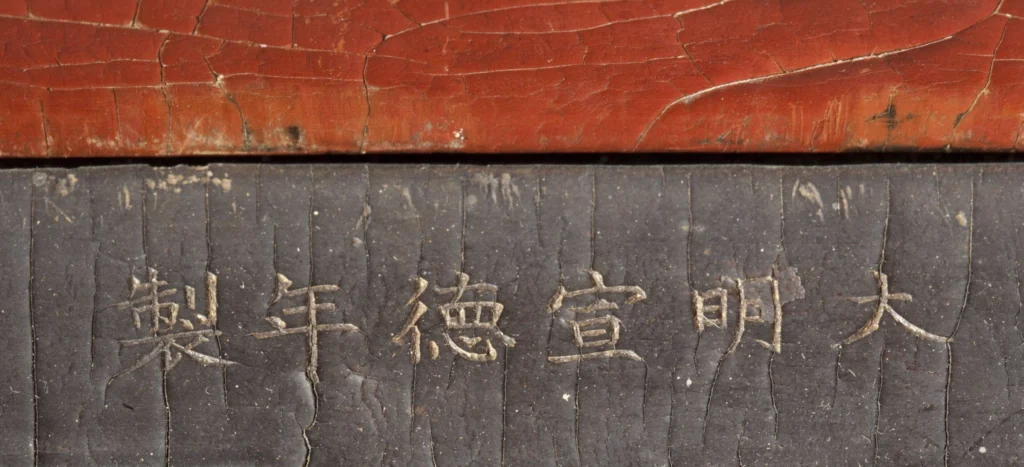

An Early Ming Lacquer ‘Dragon and Phoenix’ Table, Xuande Mark and Period

This is one of the most significant examples of Chinese imperial lacquer and is unique, as no other piece of early 15th century early lacquer on this scale exist. Most pieces of early 15th century lacquer tend to be smaller utilitarian vessels such as dishes and boxes. The manufacture of this piece was most likely far too labour intensive to have allowed many examples to have been made. The carving is absolutely superb especially to the upper surface, which depicts the dragon and the phoenix, representing the emperor and empress. For a piece that is 600 years of age, it is in remarkable overall condition.

A Large Imperial Cloisonné Enamel Ice Chest, Qianlong Period (1736-1795)

This large and imposing vessel would have been used for carrying and storing ice, which would have been stored underground at the Palace in the hot summer months. Large pieces like this with kneeling attendant figures are rare and the intricate work of casting the form and enamelling and gilding the surface would have taken many months to produce.

Cloisonné Enamel

What is it? How was it made?

Chinese cloisonné enamel was usually applied to the surface of a metal vessel, most commonly bronze. Metal wires were initially soldered onto its surface, which formed the outlines of the intended design, thus creating cells or ‘cloisons’, as they were known. Different coloured enamels were then applied within these cells and the piece was fired in a kiln. After firing, the excess enamel was then polished down to the metal wires, thus creating the coherent decoration. Most Chinese cloisonné enamel pieces from the Ming and Qing dynasties have pale blue grounds and are usually decorated with lotus.

Collecting

The ‘Ruling’ displays also encompass collecting from an imperial perspective and this lacquer display cabinet clearly illustrates this. The cabinet is 116cm high, so would have most likely have have been used by the Emperor Qianlong in the more intimate surroundings of his imperial appartments. The cabinet is displayed with a number of decorative objects, as it would have been used during his reign. The exterior is carved with a figurative scene to the pair of doors and animals to the two small drawers. All are bordered with a band of peony scroll.

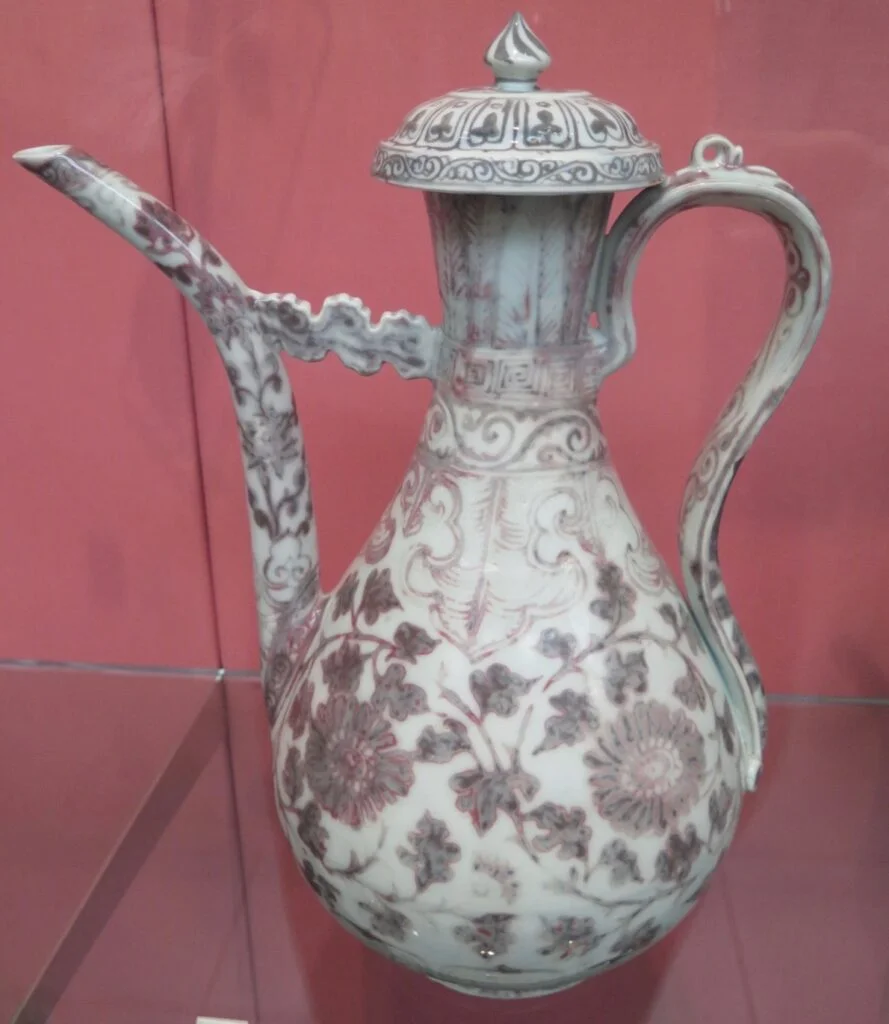

Some Ming imperial ceramics illustrating the differing styles of decoration from three reign periods. Copper-red was used quite extensively during the Hongwu reign (1368-1398) due to a shortage of cobalt during this period. This kendi, or water pouring vessel is particularly successful in the potting of its compressed spherical shape and its copper-red decoration, which is very vivid. Copper-red was particularly unstable during its firing at this time and most pieces one sees tend to have some degree of discolouration (to a grey hue).

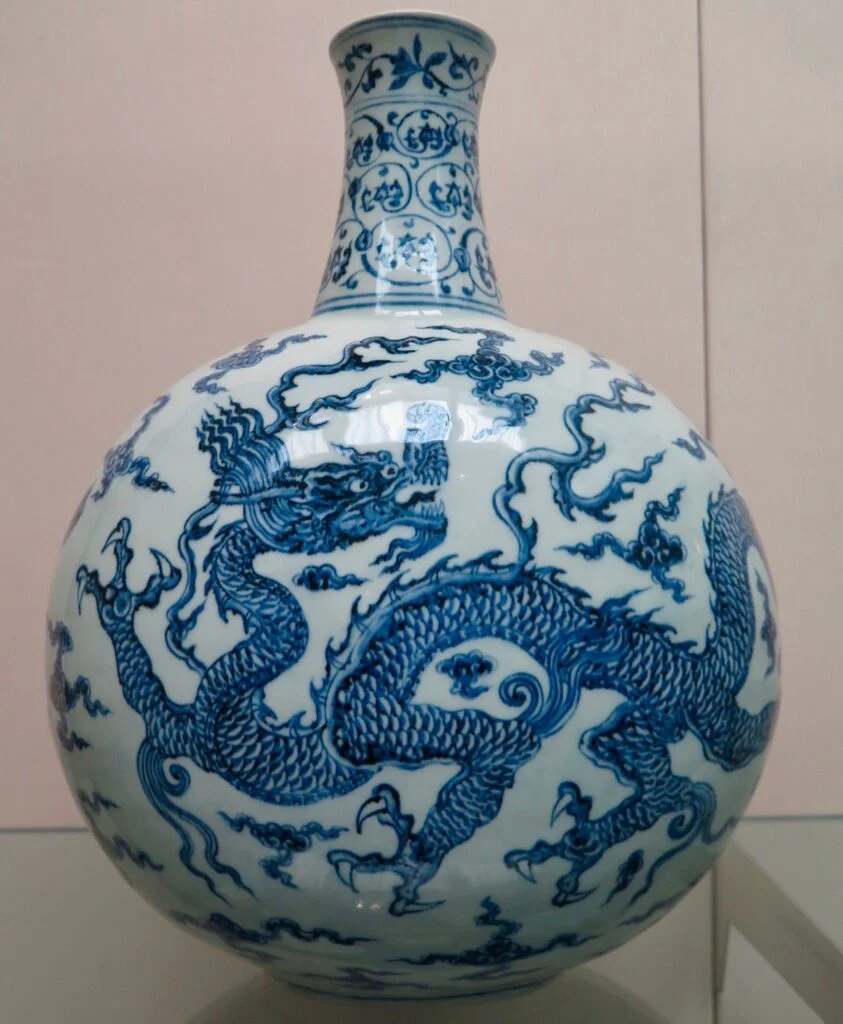

The large early Ming Dynasty, Yongle period (1402-1424) blue and white ‘dragon’ flask is similar to one in the Percival David Collection that we looked at during our visit to the British Museum. The potting is really bold and the dragon is painted in an animated pose with its head turned backward. The artist has achieved a successful variation of tones of blue by the thickness of the application of cobalt to the body prior to it being glazed and fired.

The later Ming Dynasty Jiajing mark and period (1522-1566) underglaze blue and enamelled ‘dragon’ box and cover is particularly rare in this colour combination and depicts a dragon to the upper surface of the cover striding amongst ruyi-shaped scrolls.

Central Area of the Gallery

The central area of the gallery diverges slightly from the main themes of the displays in that it has four cabinets, all focusing on the tripod vessel – the Ding. Through this vessel themes of ritual, antiquarianism, international artistic influence and authenticity are explored.

The central area was also designed to display objects being made in China today and currently a work by Shao Fan (1964-) ‘Project No. I of Year 2004’, CHAIR is being shown, which depicts an ‘exploded’ Ming style chair, with clean geometric plates of acrylic.

With this more interactive approach to the gallery, the idea of an item to touch was introduced to give gallery visitors the opportunity to experience the tactile qualities of high fired porcelain. Some concerns were expressed at the time about the safety of having such an object on display, but the large Ming Dynasty Jiajing period (1522-1566) blue and white double gourd vase has been safely in situ for 30 years. The metal label below is in braille, English and Chinese, with the former illustrating the intention to make this display accessible to the visually impaired.

Eating and Drinking

The theme of eating and drinking comprises 5 displays that are situated to the west side of the gallery and includes pieces made from bronze, jade, stoneware and porcelain from the Shang dynasty to modern day.

Living

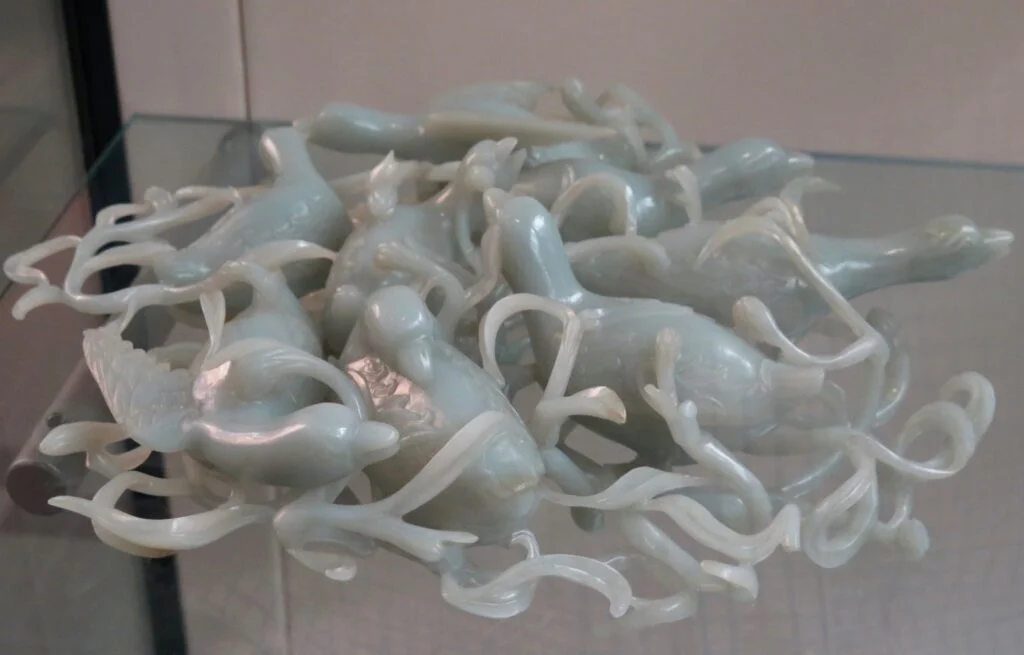

There are two vertical display cases flanking the central area of the gallery which contain objects that represented animals in nature

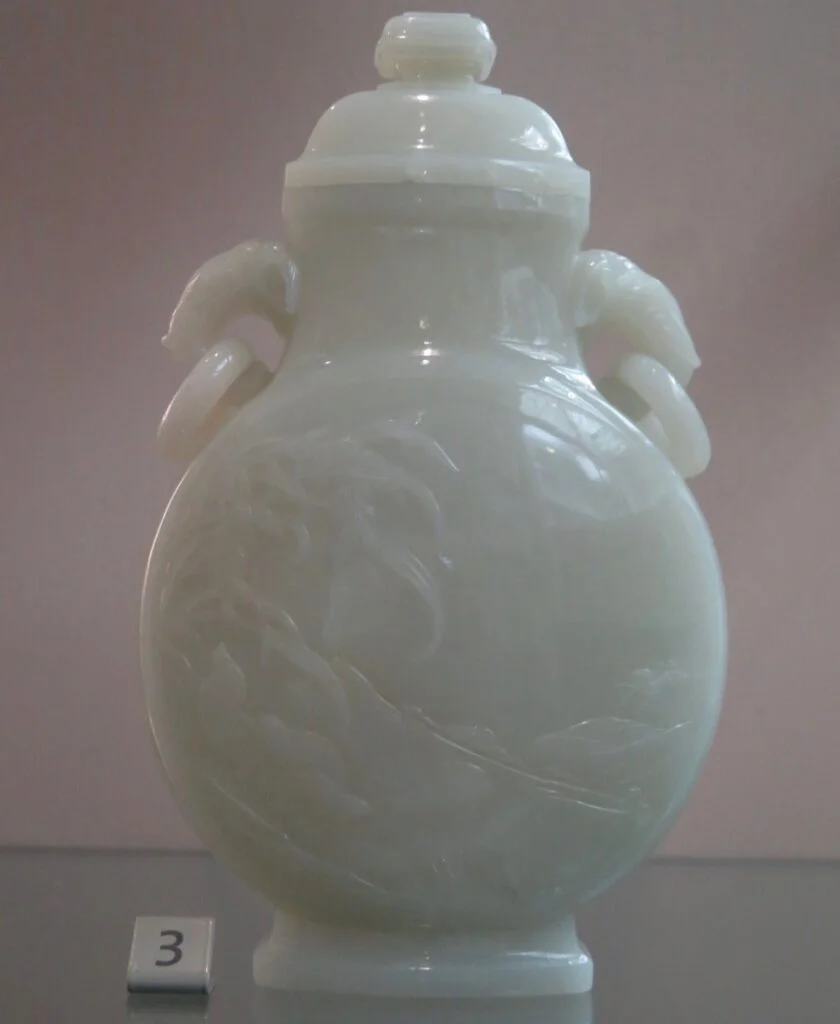

Jade

A number of pieces in this cabinet are made from jade. Jade is one of of the hardest minerals known, after diamonds. It cannot be carved, but has to be abraded with a lathe, which is a very slow and laborious process.

There are two types of jade, that is nephrite and jadeite, which each have a different crystal structure and a different appearance. Jade has traditionally been more valued to the Chinese than gold or silver.

White coloured jade is specifically sought by collectors today, as well as yellow, which is rarer. Jade was mainly worked into utilitarian or decorative vessels and miniature sculptures of animals or the human figure.

Temple and Worship

The main religions in China have historically been Buddhism and Daoism.

Buddhism

Buddhism was brought to China by Buddhist monks from India during the latter part of the Han dynasty, around 150 AD. Buddhism attracted many Chinese people to its teachings as their parables focused more on bettering oneself rather than a specific group or class of people.

A Gilt-Bronze Figure of Buddha Shakyamuni, Ming dynasty, circa 1500

The exceptional size and quality of this gilt bronze figure would have been very difficult to cast successfully. It depicts the Buddha Shakyamuni (the image of the historical Buddha as he received enlightenment) with his right hand in the bhumisparsa mudra (earth touching) pose, which is supposed to represent the moment when he overcame evil (The Goddess Mara) and asked the earth to act as a witness to this.

There is an area to the lower front of the base, where it is quite possible that the reign mark had been erased. It has been dated 1500-1600, but it is possible that it could be somewhat earlier than this. The gilding is in incredibly good condition and has a wonderful, warm and rich tone.

Daoism

Daoism has been connected to the philosopher Lao Tzu, who around 500 B.C.E. He is assumed in writing, the Tao Te Ching, the main book of Daoism The basic idea was to enable people to realise that, since human life is really only a small part of a larger process of nature, the only human actions which ultimately make sense are those which are in accord with the flow of Nature — the Dao or the Way.

A Painted and Gilt-Wood Figure of the Bodhisattva Guanyin, Jin dynasty, circa 1200

This beautifully carved figure sits gracefully in Royal Ease or lalitasana. As with most sculpture, the face is the most important part of the subject and in this example it is very realistically portrayed. Guanyin has somewhat full cheeks and small lips, with quite a prominent nose. Her eyes are half closed, as she gazed down in contemplation. The figure wears an elaborate headdress, body jewellery, a scarf draped over her left shoulder and a dhoti that falls in folds to the rustic seat.

Burial

This section of the gallery dates from the Neolithic period to the Ming dynasty and pieces are displayed chronologically.

What purpose did burial objects serve? What belief system did the Chinese follow, that necessitated artisans and potters to spend so much time creating objects for people that would never see them?

Traditionally there has been a tendency amongst Chinese people to avoid burial objects, partly due to superstition and the association with bad luck. However, it is also a natural human response to avoid the idea of one’s own mortality.

As with most human cultures, there was, amongst the Chinese, a belief in the after life and the idea of mingqi (spirit objects). The most significant example of this is the tomb warriors for the Qin Emperor at Xian (221-226 BC), where 7000 warriors and around 100 wood chariots were buried with him.

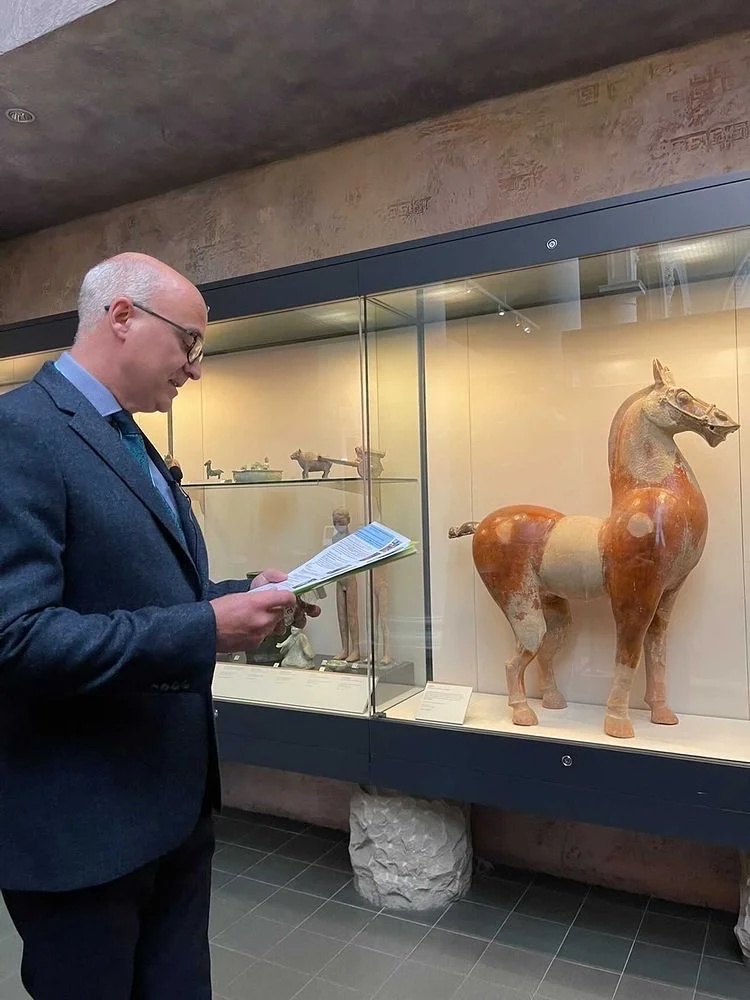

By the Han dynasty, pottery figures replaced the practices of human sacrifices, which had originated in the Shang dynasty. Now, pottery figures representing attendants, servants, entertainers and animals were placed with the deceased. More elaborate tombs developed from the Tang dynasty, which often comprised guardian figures (lokhapala), earth spirits, camels, horses (glazed or unglazed), which varied in size and quality.

Conclusion

The refurbishment of the gallery had its critics at the time, the traditionalists who preferred to see museum displays classifying pieces by type and date – where one had to do the work of developing the eye (connoisseurial approach). However, despite its critics, it is clear that this approach of placing pieces in a cultural historical context, allowed Chinese art to become more accessible to a far wider audience than it had previously.

Part 2

4th Floor Ceramic Galleries (Mainly 137)

Historical Layout

In 1909 a new building, designed by Sir Aston Webb, formed the grand southern front of the Museum along Cromwell Road. 11 Galleries were created on the fourth floor that were lit from above using special roof glazing.

My first memories of coming to the galleries were back in the late 1980s. At this time, These were laid out chronologically and by region, with Middle Eastern ceramics at one end, Asian at the other and European and the British collections in between. It was a somewhat overwhelming experience walking through through the galleries, which seemed like they would go on forever with the thousands of objects that they displayed.

Refit Completed in 2010

Two architectural firms were consulted as part of the museums FuturePlan, for the ongoing programme of restoration and rebuilding. The galleries were completed in 2010 and the very tall display cabinets allowed space for around 26,500 objects from the collection to be viewed.

Three Themes in the Renovated Galleries:

1. Historical and Geographical links through trade – especially illustrating blue and white ceramics.

2. Sense of the Exotic – Europe-Porcelain Rooms.

3. Materials and Techniques – How were ceramics made? and some pieces made today.

Some imperial Qing pieces will also be highlighted from this gallery, which were initially from two private collections.

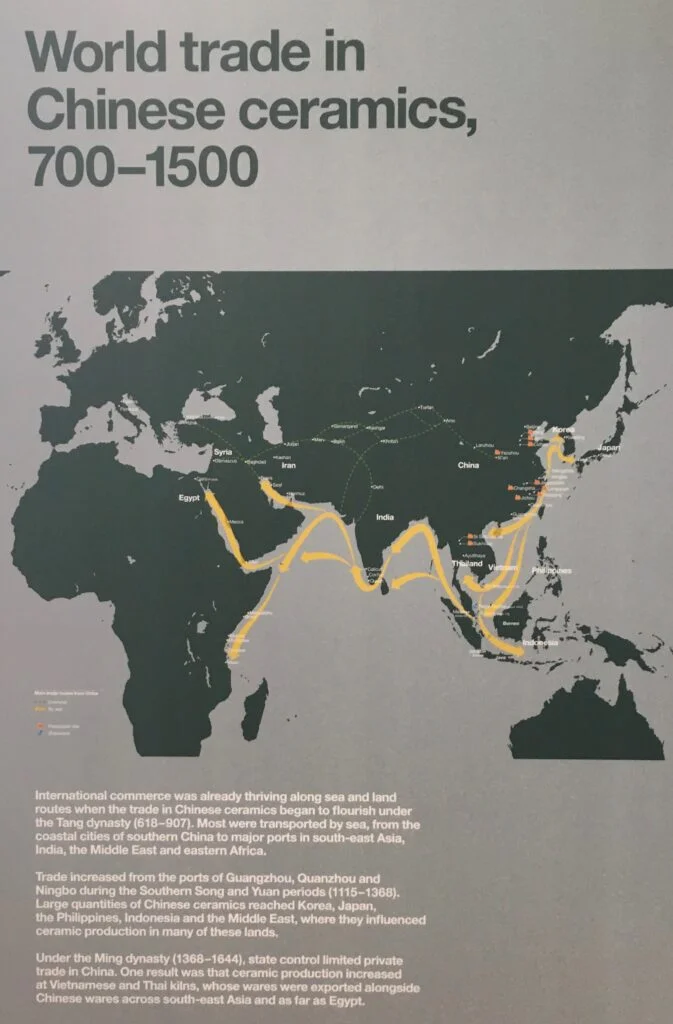

1. Historical and Geographical Links Through Trade

On the upper walls of Gallery 137, there is a time line that runs throughout its length and pieces are arranged chronologically within it. The gallery also displays the stylistic interrelationships between ceramics of different countries and the connections between them.

14th-15th Century

A number of cabinets illustrate the Islamic influences on China during this period, in terms of their shapes. They also display the influences that Chinese wares were to have on Middle Eastern ceramics.

Dragon Flask, Yuan dynasty

Influenced by Islamic metal shape. This is a very rare form and there is one in Topkapi in Istanbul and one was sold by Doyle auction room in New York in 2003.

Early Ming, Yongle Period Lotus Jar

This jar displays a really high degree of quality in its painting of the a continuous lotus scroll. The design is successfully incorporated on to the wide bodied jar and the painter used a deep blue colour cobalt. The ‘heaped and piled’ effect was created by thick layers of cobalt that leach through the glaze during firing, creating an almost black colour to these parts of the surface.

Large Pheasant Dish, Yuan dynasty

Its large size is dictated by Middle Eastern communal style of eating.

16th/17th/18th Century

This period saw the beginnings of sea borne trade and the Portuguese were the first to dominate this in the 16th century. They were succeeded by the Dutch in the 17th century, through the Dutch East India Company (VOC).

2. Sense of the Exotic in Europe – Porcelain ‘Cabinets’

From the 1680s onwards, European aristocrats displayed their porcelain crammed in rooms or ‘cabinets’ as they were known. Some pieces in these displays could be of high quality and valuable, but on the whole this was not the case, as the overall effect was more important than the sum of its parts.

It was a way for aristocrats to show their new wealth and power with the display of these new exotic luxury goods that had been imported from China.

Qing Imperial Porcelain Highlights From the Galleries

George Salting (1835-1909)

George Salting was an Australian born art collector who inherited his wealth from his father, Severin Kanute (Knud) Salting (1806–1865), who had emigrated from Denmark and had considerable business interests in Sydney. Salting collected widely from paintings to Chinese porcelain and his bequest stipulated that his collection be displayed together in one gallery, which they were until the recent refurbishment.

William Giuseppe Gulland Gift (1883)

Gulland spent most of his life as a merchant in Asia, where he developed a keen interest in Chinese porcelain. In 1905 Gulland presented to the V&A 180 pieces of porcelain. The remainder he bequeathed to the Museum subject to the life interest of his wife, Julia Clementina.

Definitions of Chinese terms to 18th century imperial Wares:

Yangcai

Foreign colours that were produced at the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen, which usually have underglaze blue reign marks.

Falancai

Foreign colours – where the porcelain blanks were fired at Jingdezhen and then sent to the Beijing workshops. These usually have enamel reign marks and are usually the pieces of the highest quality.

Fencai

Powdery colours – pale pastel colours.

3. How Were They Made? And Contemporary Ceramics at Jingdezhen

Concluding with contemporary pieces which have a sense of modernity and humour – McDonalds arches.

Conclusion

The T.T. Tsui and the 4th floor ceramics galleries were updated significantly in 1991 and 2010 respectively. Both reflect a more modern approach to representing objects in a museum setting – illustrating themes on how these objects were made, how influences in designs were transmitted globally and how objects were used in confirming power and their use in religious ceremonies and burial.

This contextual approach was part of a late 20th century movement to make sense of objects from a social historical context, rather than just a formal and stylistic basis that had been the norm prior to this. This more democratic approach has no doubt made the museum’s displays more accessible to a wider public and thus has helped to succeeded in fulfilling its main primary goal of communicating with its public.

Notes

1. Kerr, Rose, Gallery Report, The New T.T. Tsui Gallery of Chinese Art at the Victoria and Albert Museum, Otiental Art, Summer, 1991, p. 115.

2. Ibid, Kerr, Rose.

3. Collections.vam.ac.uk website.