Imperial Ming and Qing Porcelain

From the early Ming Dynasty, porcelain was manufactured to order at the Imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province. The technical innovation of painted underglaze copper red and blue, deriving from cobalt had begun in the Yuan Dynasty (1275-1368) and reached a high level of sophistication by the middle of the 14th century. (Fig MQ1. and MQ2.) Large scale pieces were made to order for the Middle Eastern market, some of which followed earlier Islamic forms. However the styles of the painted designs were very much of Chinese origin, often depicting dragons, phoenix, fish, peony, and lotus. (Figs MQ1. and MQ3.)

Photograph © Brooklyn Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

Other technical innovations were developed during the early Ming Dynasty, such as doucai or ‘dove tailed’ decoration, where underglaze blue outlines of the decoration were firstly painted onto the body of a piece. This was then glazed and fired at a temperature above 1360’C and was followed with the application of overlaid enamels, that filled in the areas left by the outlines. The piece would then fired a second time, but this time at a lower temperature in a muffle kiln.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © Sotheby’s

Photograph © British Museum.

The first examples of these were seen in the Xuande reign (1426-1435), but the finest quality wares were produced in the Chenghua reign (1465-1487) which can be seen on the iconic chicken cups (Figs MQ4.) The potting of these wares is particularly fine and the colour of the white ground is a milky off-white and the enamels are of a warmer tone than compared with 18th century copies. (Figs MQ5. and MQ6.)

The wucai technique differs from doucai in that the underglaze blue forms part of the overall design and not just its outlines. The high point of production of this was in the latter part of the Ming Dynasty under the reign of the Jiajing (AD 1522-66), Longqing (AD 1567-72) and Wanli (1573-1619) Emperors. (Figs MQ7. and MQ8.)

Further technical innovations were achieved in the Qing Dynasty, with the development of the ‘famille verte’ palette, which evolved out of wucai decoration in the wares of the Chongzhen (1628-1644), Shunzhi (1644-1661) and early Kangxi periods (1662-1722). From around 1700, an underglaze blue was replaced with an over glaze enamel, (Fig MQ9.) allowing the decoration to be applied over the glaze in one firing. This would have cut down on wastage as any mistakes painted onto the glazed fired surface could now be wiped off and re-applied.

Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

During the latter part of Kangxi’s reign, further innovations of the use of a pink enamel from a colloidal gold solution, an opaque white enamel from lead arsenic and an opaque yellow enamel from lead stannate was developed in the ‘famille rose’ palette which allowed more tonal gradations to create greater three dimensional effects. (Fig MQ10.)

These developments were continued during the Yongzheng period (1723-1735) under the supervision of Tang Ying (1682-1756) who was appointed from the Royal Household to oversee production at Jingdezhen. Under his watch, the quality of production reached its peak with the fineness of the ceramic body and its potting, the originality and execution of designs and the level of technical skill of the glaze painting. (Figs MQ11.)

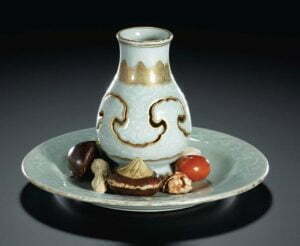

Innovations continued under the Qianlong Emperor (1736-1795), who took a particular interest in production. Under his reign, new shapes were produced, such as pierced double walled vases, as well as revolving and larger scale vases. Highly elaborate designs in bright, almost gaudy colours were produced, often with sgraffiato grounds, where floral brocade designs were painstaking incised through a coloured ground to a white fired body below. (Fig MQ12.) Qianlong also had a fascination for tromp l’oeil and produced wares simulating other materials or real objects, such as books or fruit. (Fig MQ13.)