Song Ceramics

The ceramic art of the Song Dynasty (960-1275) has historically been divided into two distinct periods of manufacture, the Northern Song (960-1127) where the court was located at Kaifeng and the Southern Song (1127-1275) where the capital shifted south to Hangzhou after the north was over run by the Jurchen tribes who established the Jin Dynasty (1127-1234).

The wares of the Song Dynasty were primarily stoneware, except for the porcelaneous Ding and Qingbai wares. The former were produced in Jiancicun in Quyang County, Hebei province and the latter at a number of locations in Jiangxi province including Jingdezhen, where porcelain production was to be later centred.

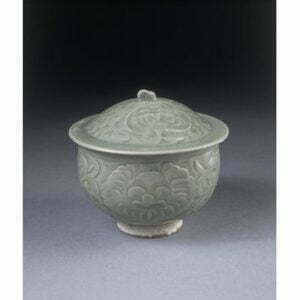

The Chinese refer to the five classic wares of the Song Dynasty: Jun, Ding, Guan, Ge and the rarest of all – Ru. These wares reflected a subtle and sophisticated aesthetic, where the beauty of the object primarily lay in its form and the effects of its glazes which were usually of mono-tonal colour. Carving or moulding could further enhance this aesthetic as can be seen in Ding wares, where the best examples illustrate a spontaneity of carving (Fig S1.) or a really crisp rendition of a moulded design (Fig S2.) (the latter are usually dated to the Jin Dynasty) and subjects ranged from lively dragons to fish and lotus.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © Design Museum, Copenhagen.

Photograph © Victoria & Albert Museum.

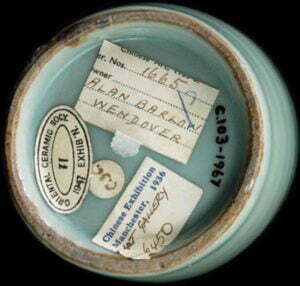

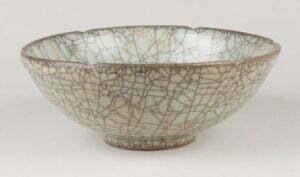

Ruyao are the rarest and most treasured of all the wares in Chinese ceramics. It is believed that they were made for a very short period of around 20 years roughly from 1086 to 1106 at the kilns in Ruzhou, in modern Baofeng county in Henan province. They have attained almost mythical status amongst collectors as they are virtually unobtainable. Only 6 examples have come up for sale at auction since 1940 and only 87 heirloom (not excavated) examples exist, with only 36 of these outside of China. The most successful examples exhibit a subtle turquoise colour and a translucent crackle that refracts light. (Fig S3.) The crackle is created by the glaze shrinking at a slightly faster rate than the body in the firing process. These wares are also known by their characteristic ‘sesame’ seed spur marks.

Other significant wares were the celadons made at the northern Yaozhou and southern Longquan kilns, the former of which also relied on carved and moulded decoration (Fig S4). The best examples of Longquan ware combined a refinement of shape with a bright, almost turquoise-green coloured glaze, known as ‘Kinuta’ to the Japanese, who held these wares in very high esteem and often used vases (Fig S5.) in this ware for displaying flowers in the tokonoma alcove of the tea ceremony room.

Photograph © Victoria & Albert Museum.

Photograph © Victoria & Albert Museum

Photograph © Victoria & Albert Museum.

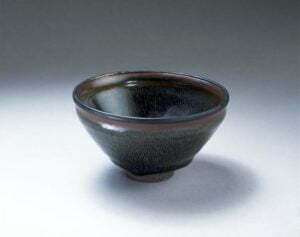

Longquan tripod incense burners were also popular in Japan (Fig S6) and were often mounted with silver pierced covers. Jian wares were also held in high regard by the Japanese and some of the finest ‘Tenmoku’ bowls are held in collections as ‘national treasures’ and display wonderful glaze effects in silvery-blue streaks or circles (Fig S7).

Photograph © Victoria & Albert Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.

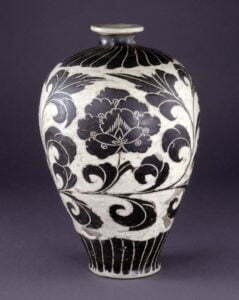

The exception to the monochrome wares produced in the Song Dynasty were those produced at the Cizhou kilns. These were made in numerous kilns in the north and combined the techniques of painting and carving through black and white slips. The meiping (Fig S8.) and guan jar shapes particularly suited designs such as carved peony and painted fish amongst waterweed respectively. Detailed painted designs depicting figures or flowers could be found on pillows (Fig S9), where the upper surface acted as a flat ‘canvas’ for the artist.

Photograph © British Museum.

Photograph © Metropolitan Museum.

Photograph © British Museum.